STANLEY KUBRICK: An Exploration into the Creative Process of a Design Master

Renowned for his painstaking attention to detail — GATA deconstructs the lengths this legendary director travelled in order to achieve his artistic vision

The word “genius” is often thrown about in film critic’s circles to the point that it has become devoid of much of its meaning, but in the case of iconic director Stanley Kubrick, you would be hard-pressed to find anyone willing to argue the point. From the unsettling supernatural horror of The Shining to interplanetary exploration in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick has defied classification, conjuring cold, sterile, yet beautifully detailed worlds that have spanned multiple genres.

From meticulously researching the width of streets in New York to cataloguing the furnishings of doorframes or the creation of thousands of design iterations for his eventual movie posters— it was this deep obsession with world-building that would be the foundation for his design and creative process. No stone was left unturned when it came to creating an image on the screen that would perfectly mirror the mood of his internal vision.

A Clockwork Orange (1971) © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

An Education in the Streets

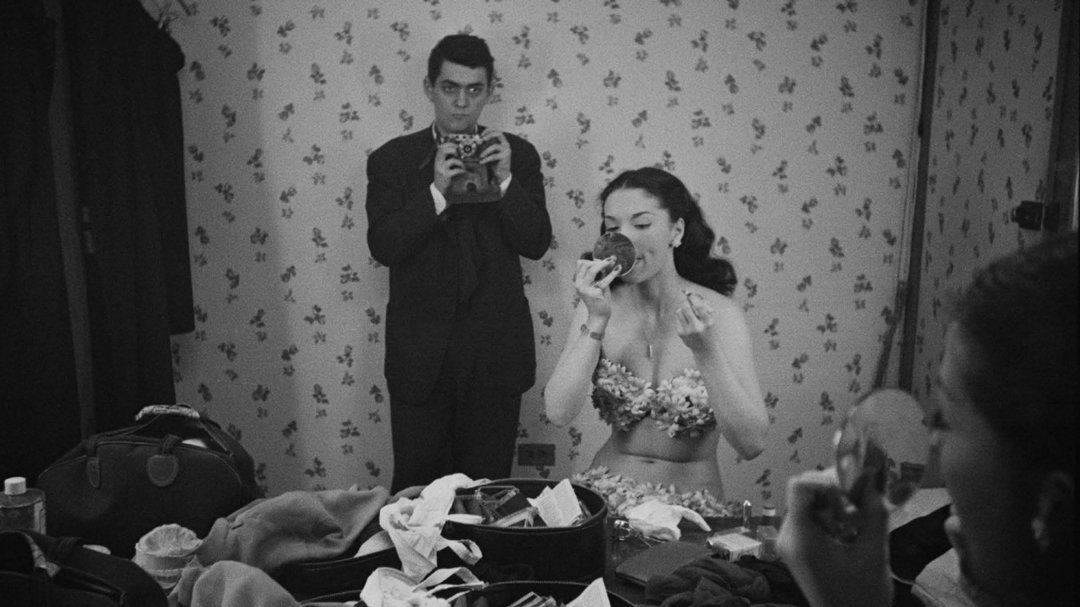

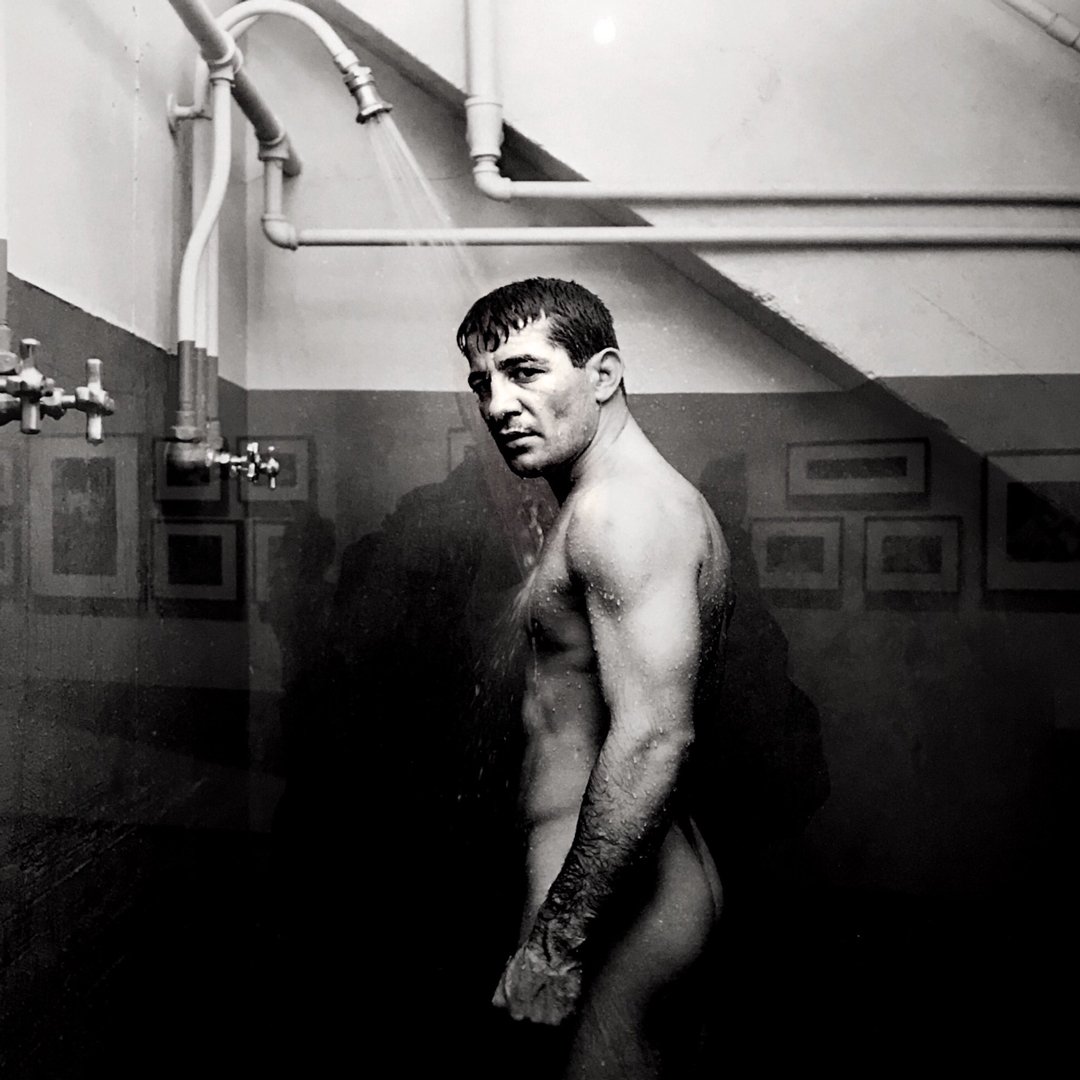

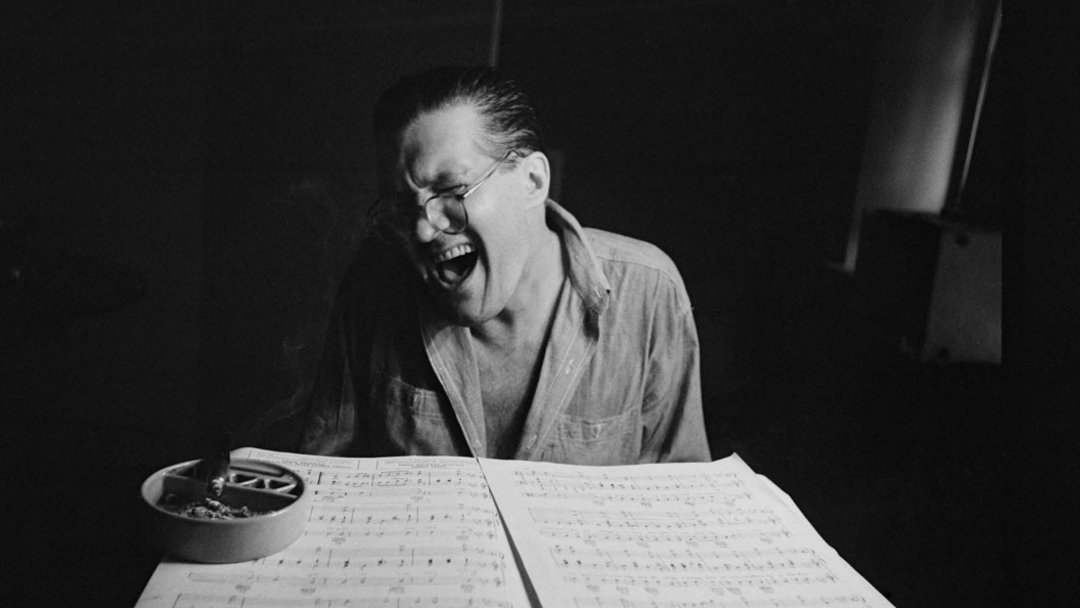

Born in the Bronx New York, in 1928, from a young age, Kubrick was influenced by visual storytelling. It is telling that his first job was working as a staff photographer for LOOK magazine, where he developed a strong neo-noir style of photography influenced by the film genre that he adored as a child. Utilising dark and brooding lighting to tell the personal and intimate stories of the residents of New York, his style leaned towards the cinematic, imbuing his photos with drama and intentional atmosphere that was at odds with the straightforward composition and naturalistic lighting that was common in photojournalism at the time.

Another key passion during his early years was his love of the game of chess. During the 1950s Kubrick could often be found playing in Washington Square. His games would often span from 12 at noon until about 12 midnight, and through participating in tournaments and games for money, it was reported that he was able to earn around 20 dollars per day on this hobby alone. However it was not just financial reward that was the only positive to come from this game, Kubrick has been reported on numerous occasions to highlight the important lessons that the game taught him in regard to filmmaking and problem-solving. This minute attention to detail, formulating moves in advance and being both strategic and objective when assessing problems that would come to serve him to great avail in his career as a film director.

“Chess teaches you how to control the excitement that you feel when you see something that looks very good. It teaches you to think before you act, and to think with the same objectivity when you are in trouble”

2001: A Space Odyssey © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

Meticulous Set Design

In the 1960s, Kubrick relocated to England in the wake of filming Lolita. A big reason behind his move was the desire for creative control over his movies, away from the prying hands of Hollywood studio executives who may not have been completely on board with his meticulous attention to detail and need to control every aspect of design. This now legendary obsession with the finer points of his movies is no clearly demonstrated than his final film Eyes Wide Shut. It is reported that in the pre-production stage of the movie Kubrick sent assistants, to New York with the sole task of measuring the width between mailboxes on the streets so that he could meticulously recreate them on his set in the UK.

Some may ask is this the behaviour of a creative genius or that of a meglomaniac? Yet in defence of Kubrick you only have to watch a few minutes of Eyes Wide Shut, to grasp the logic behind his madness. The film’s presentation of artifice creates a dreamlike quality and hypnotic atmosphere that may not have been possible if it was filmed solely on location.

Eyes Wide Shut (1999) © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

Eyes Wide Shut (1999) © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

“I do a tremendous amount of planning and try to anticipate everything that is humanly possible to imagine prior to shooting the scene, but when the moment actually comes, it is always different.”

In Dr Stangelove, his preference for thematic architecture and set design is evident in the now legendary war room. Designed by Ken Adam, who was at the time most famous for his part in constructing the aesthetic that would come to define the lairs of James Bond villains—the war room was an immensely impressive set that would overshadow the rest of the film. Interestingly when America’s ex president Ronald Reagan was inaugurated, he was famously said to have been extremely disappointed with the real war room in the White House at the time.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) © Sony/Columbia Pictures Industries Inc.

Cinematography and the art of mis-en-scene

Kubrick’s design genius was not limited to just an impressive use of set design but also in his masterful use of cinematography and lighting. In The Shining, Kubrick uses a deliberate and controlled approach to his mis-en-scene, manipulating each element of the visual storytelling to create the desired effect upon his audience. Take for example the recurring motif of mazes from the film. Multiple scenes feature lines, either literal or symbolic, often surrounding our characters adding to the foreboding threat. In one scene with Danny in which he is playing with his toys, he is encircled by the geometric patterns of the carpet, surrounded in a high key lighting, at odds with the more traditional and moody contrast heavy lighting of horror. It is this unsettling and novel use of the elements contained within his picture that separated Kubrick from his contemporaries and has granted him legendary status within the history of cinema.

The Shining (1980) © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

The Shining (1980) © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

In Barry Lyndon, Kubrick’s 18th epic tale of a rogue ascending the social ladder of 18th century Britain, Kubrick pushed the limits that had been seen in regards to natural lighting. In one dinner scene, Kubrick was adamant about only using candles to light his actors, the only problem being that no lens was able to properly catch the image due to the low level of light being emitted by the candles. this resulted in Kubrick contacting NASA, and buying three Carl Zeiss lenses with extremely large apertures that were able to capture the low lighting conditions. These lenses were intitally comissined by NASA with the goal of capturing the dark side of the moon during missions into space. It was this attention to detail and uncompromising mindset that remained within Kubrick for every one of his feature films.

Barry Lyndon (1975) © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

Music Takes Front Stage

Music also played a large role in the films of Kubrick. Often in cinema music plays a supportive role, a means of accompanying the images or amplifying the mood of the scene. However Kubrick often used a thoughtful approach to his sound design, with the score taking front stage during his films and overshadowing the images on screen. Take for example the use of music in 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the dawn of mankind segment, the music is ominous and haunting, amplifying the brutal existence of the hominids, yet when we get to the famous image of the tossed bone, cutting to a space station we are greeted with an extreme shift in tone with the introduction of Johann Strauss's "Blue Danube Waltz". This astral ballet overwhelms the screen, filling the audience with a sense of progress and optimism, a far cry from the first act of the film. Kubrick cleverly uses juxtaposition as a tool here, creating disharmony and tension within his film. It’s as if music has taken on the role of an actor within the film, narrating the story and guiding the audience down lanes Kubrick wants to take us, shaping our feelings without consent.

2001: A Space Odyssey © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

Legacy

Looking back on the filmography of Stanley Kubrick, we can see that he has created so many memorable worlds that have heavily influenced not just the realm of cinema, but pop culture and design as a whole. While cinema had auteurs and dedicated creators before him, it’s very interesting to imagine what the landscape of Hollywood would be like if he hadn't made his films. Almost every single major Hollywood director working today has in some form of the other paid tribute to Kubrick, citing him as a huge influence on their work. Would there be the interplanetary odyssey of Interstellar without 2001, the frozen paranoia of John Carpenter’s The Thing without The Shining or the famous ear scene from Reservoir Dogs without Alex’s rendition of singing in the rain from A Clockwork Orange? Every creator leaves a mark in their respective field when they pass, but it feels like the shadow of Kubrick is one that very few directors ever escape from.

Full Metal Jacket (1987) © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc