Harmony Korine - An Unstructured Reflection of Life

For decades, the art of film has largely been bound to conventional structures, be it character or plot. One director who sought to completely disrupt this was Harmony Korine. The cult and controversial artist has stated that he views the old format of film making as tired and outmoded, and seeks to explore and coax out a more unique corner of the world through inviting viewers to tour through his own artistic process; total unconstraint.

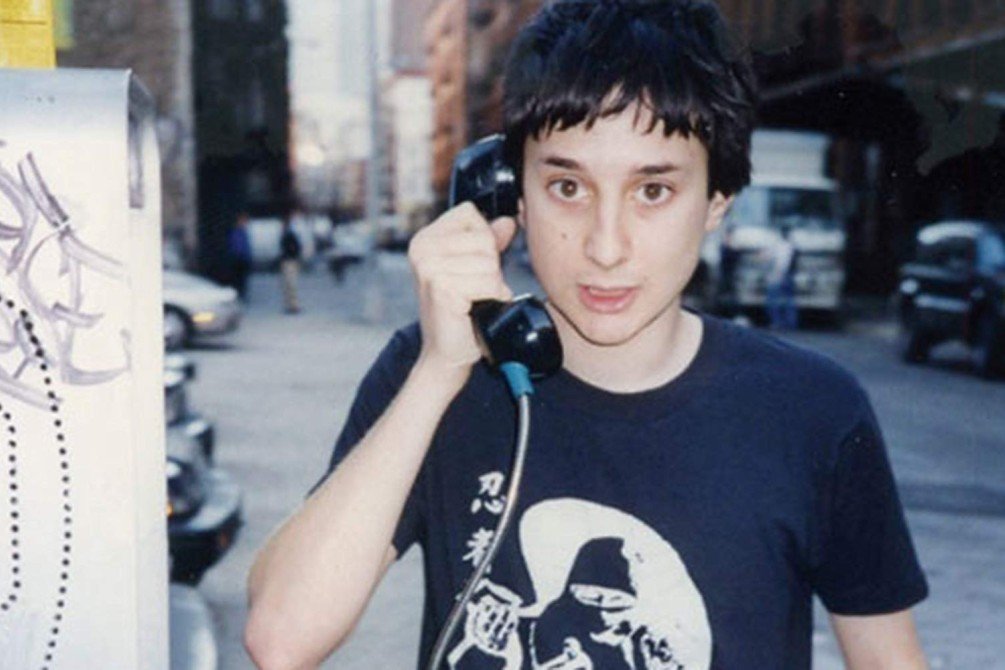

Harmony Korine’s background is a mosaic of artistic endeavours and accomplishments, spanning from filmmaking to writing to painting. While most of us are most familiar with his roles within film (be it as a director, writer or actor), the area of film was not one which immediately took his interest. Having been raised in a commune in the American countryside, and later moving to Nashville, Tennessee, Korine spent much of his time drawing and writing. However it wasn’t until a high school teacher read one of his short stories that the avenue of filmmaking became a plausible option for him. The teacher asked the young Korine if he could make this into a short film, and fundraised a couple of thousands dollars for it once he agreed. With his father helping him to manage the camera, the young teen’s life path was changed forever.

Not long after this, a 19-year-old Korine met photographer Larry Clark while skating with some friends in Washington Square Park. The photographer took a liking to Korine and was impressed with his knowledge, so he asked the teen to create a script about skaters, which included the AIDS crisis which was looming over the young generation at the time. Korine reportedly told Clark, "I've been waiting all my life to write this story,” and within three weeks, he had written the feature length film Kids (1995). Kids is based in New York in the 90s and follows the drug and sex-filled lives of a group of teen skaters for a day. The ninety-minute film resulted in a new production company being created just to release it due to the NC-17 rating that it would receive if it was released under a company that was signed to the Motion Picture Association of America. By doing this they sidestepped cinema which were be unable to screen NC-17-rated films, and newspapers who would not have been able to run advertisements for them. As well as this, the film’s bold move in tackling the AIDS crisis was also a notable turning point in cinema as this particular topic lay mostly untouched by media at the time due to it being associated with members of the LGBT community, sex workers and drug users who were all largely shunned by society in the 90s. The movie quickly gathered steam and became a huge cult success, resulting in the teen protégé successfully punching his way up into the upper echelons of the film world, and in an undeniably unique way.

Kids (1995)

One aspect which immediately leaps out in Kids is the loose and casual direction of the film. The documentary-style footage of unaffected youths blurs the lines between fiction and reality with its relaxed dialogue and lack of a traditional film plot or structure (beginning, middle, end), resulting in such a effortlessly realistic portrayal that many viewers find it a tough watch due to its harrowing nature. The film is also almost completely void of adult presence throughout it. The kids are left unattended and unsupervised, free to roam the city with an absence of fear around any disciplinary action. However this in fact serves as a means of putting the entire focus on the unseen horror of HIV as the very real consequence for this sort of youthful nihilism. Korine states that he used Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) as the inspiration for this, telling Rolling Stone magazine that at the time “we didn’t know anything about this disease other than that we didn’t want to get it”.

“we didn’t know anything about this disease other than that we didn’t want to get it”

- HARMONY KORINE

The youthful cast also serves as a nostalgic albeit harrowing reflection of people who grew up in a similar environment as a teen, with certain characters or issues mirroring either people we knew or oneself; carefree and rebellious. Korine states, “I love people who do what they wanna do. Who follow their own rhythms... I try to make films about characters like that”. While many of the scenes of drinking, drug use and violence may have elicited some feelings of rebellion and excitement, especially as a younger viewer, the nihilism and aimless nature of the teens now serves as a chilling reminder of the consequences which this lifestyle brings as we tumble out of our youth and into a world of heightened responsibility. Talking about the characters in his films, Korine details how “There’s an inherent drama and even a tragedy to a lot of those characters. Sometimes the most creative, the most inventing of their own reality, the freest, also are the ones who find themselves in the most jeopardy.” And, while everyone may not even identify directly with the characters or their lifestyle, there is an inherent connection to the unique figures which grace Korine’s screen which has led them to nestle their way into the boroughs of our minds; Jennie (played by Chloë Sevigney’s) as a symbol of our loss of innocence, or Gummo’s Solomon, who serves as the opposite.

“There’s an inherent drama and even a tragedy to a lot of those characters. Sometimes the most creative, the most inventing of their own reality, the freest, also are the ones who find themselves in the most jeopardy.”

- HARMONY KORINE

We are again invited into a world of odd and abnormal characters in the 1997 masterpiece Gummo, written and directed by Korine serving as his directorial debut with the budget of only 1 million dollars. Deciding to film this in Nashville where he spent most of his childhood, Korine delves into a more rural setting, peering into the lives of some of the more forgotten people of the world, left untouched and uncared for in the dark but shallow cracks of society. With the films unstructured plot, unusual characters, and gritty subject matter, Gummo takes the spontaneity of Kids and raises it tenfold. Kids who spend their time sniffing glue and killing cats, a boy with bunny ears who plays the accordion in toilet stalls, and a surprisingly impassioned wrestling match with a chair, this movie sucks you in and takes you for a ride through Korine’s unique fever-dreamlike world. It is here in fact that he seems to find his beauty in the world. Korine has said that “all the characters in my movies are beautiful even the ones that I find disgusting”, which seems to encapsulate the unique aura of his films, floating somewhere in-between a dream and a nightmare.

“all the characters in my movies are beautiful even the ones that I find disgusting”

- HARMONY KORINE

Gummo (1997)

Similar areas are revisited in Julien Donkey-Boy (1999) which centres around Julien, a man with schizophrenia and his dysfunctional family. This film serves as a further attestant to Korine’s ability to envelop and emote with a limited toolbox, as it is one of the first films to be created under Danish Directors Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg’s Dogme 95 manifesto which imposes strict rules and regulations around film making such as the camera having to be hand-held and no use of artificial location or light. The film fosters an inherent sadness within it alongside some embers innocence, all rolled up into the one package that is equally as complex and confusing as it is simple, similar to the doe-eyed character Julien.

Trash Humpers (2009)

When questioned about the where his films come from, Korine firmly states that his films are not of an autobiographical nature but merely random creations, “I don’t really ever set out to make anything specific... I’m trying to search for it. Trying to make it up as I go. The movies are more about energy, or wildness, or something that’s less defined. Something that’s more magic. I don’t go in knowing.” But we have to question how much these characters and their settings do owe a debt to Korine’s past however, as while it may not be so rigidly fixed in an autobiographical sense, his past experiences are effectively what moulded the mind which gives them life. For example when talking about growing up in Nashville, he recalls how “there weren’t a lot of people. Nobody really had anything. There was a lot of eccentrics”, conjuring up similar images (while perhaps less extreme) to the scenes of Gummo. Or, his experience as a skateboarder in New York which would have greatly guided the writing of Kids and Ken Park.

Spring Breakers (2012)

Ultimately, it seems to be an innate sense of freeness which guides Korine’s work. A desire to explore the unknown layers of life, to create, and to have a conversation (even if it’s a random one). This same ethos has translated into the artists paintings, which he spends much of his time on now. When describing painting he openly confesses how it’s just “just throwing paint and just seeing where things fall.” This results in works which while drawing us in seem to have an almost unfinished aspect to many of them such as The Kotzur Gift or Clincer Feen which can’t help but evoke a familiarity to his films such as Kids and Gummo which conjure what could only be described as a sort of melancholy curiosity lingering in the air as the credits roll, leaving us satisfied but also questioning what it is that lies behind the next door. It seems this label could even be stretched over Korine’s body of work as a whole, a breath of unshackled spontaneity which leaves us curious as to what’s next. For now it seems that Harmony is unsure of the answer to this question too, but I presume that’s exactly how he likes it.

WORDS BY RONAN M