RAW MEAT AND HEAT: THE MAKING OF THE CHAIN SAW MASSACRE

More than 50 years after tearing its way into the psyche of America’s public, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre remains one of the most important films to come out from the horror genre. Its mix of gritty low-budget aesthetics and subject matter that pierced the heart of human nature terrified audiences at the time; bringing horror out of the realms of the supernatural and into the homes of the public. Horror was no longer reserved for supernatural beings such as vampires or ghosts but instead took on the forms of the outcasts, recluses and disturbed. The face of horror finally had a human element, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was a catalyst.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was significant for other reasons too. For one it was an ambitious independent movie filmed in Texas by Texans. In an industry dominated by the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, the ambition to remain in your hometown and not only challenge the establishment but strive to create something wholly original and unheard of was not something to scoff at. With an initial ambition of putting Texas on the cinematic map, the resulting film had a result that was much more profound. A legacy that would only become apparent, years after the release.

Tobe Hooper

Directed by Tobe Hooper and written in collaboration with Kim Henkel, from its outset, the film was a passion project. Before filming both Hooper and Henkel were working day jobs, producing advertisements as well as industrial and political spots, yet it was always their ambition to create something more subversive in nature. The genesis of the film lay in Hooper’s fascination with the crimes of Ed Gein, as well as the nihilistic political context that the 1970s found itself in. In the political corruption of Nixon’s Watergate scandal and the massacres and atrocities committed in the wake of the Vietnam War, Hooper came to the conclusion that “man was the real monster here, just wearing a different face…[this is why] I put a literal mask on the monster in my film.”

The production was made for an extremely low budget of approximately $100, 000, made up of a crew who, like the director, came from Texas. For many of the crew, the desire to work on the project came from a passion to create something original and groundbreaking. Away from the eyes of the big-budget Hollywood studios they were afforded a creative freedom that traditional filmmakers could only dream of. Yet with creative freedom, came an excruciatingly tight budget. A state of affairs they would come to understand all too well in the months to follow.

“One of the things that always work, one of the creepiest things a horror film can have, is the ambiance of death. Like the way Frankenstein’s monster is put together by pieces of dead bodies. That’s why I opened the film in a graveyard. ”

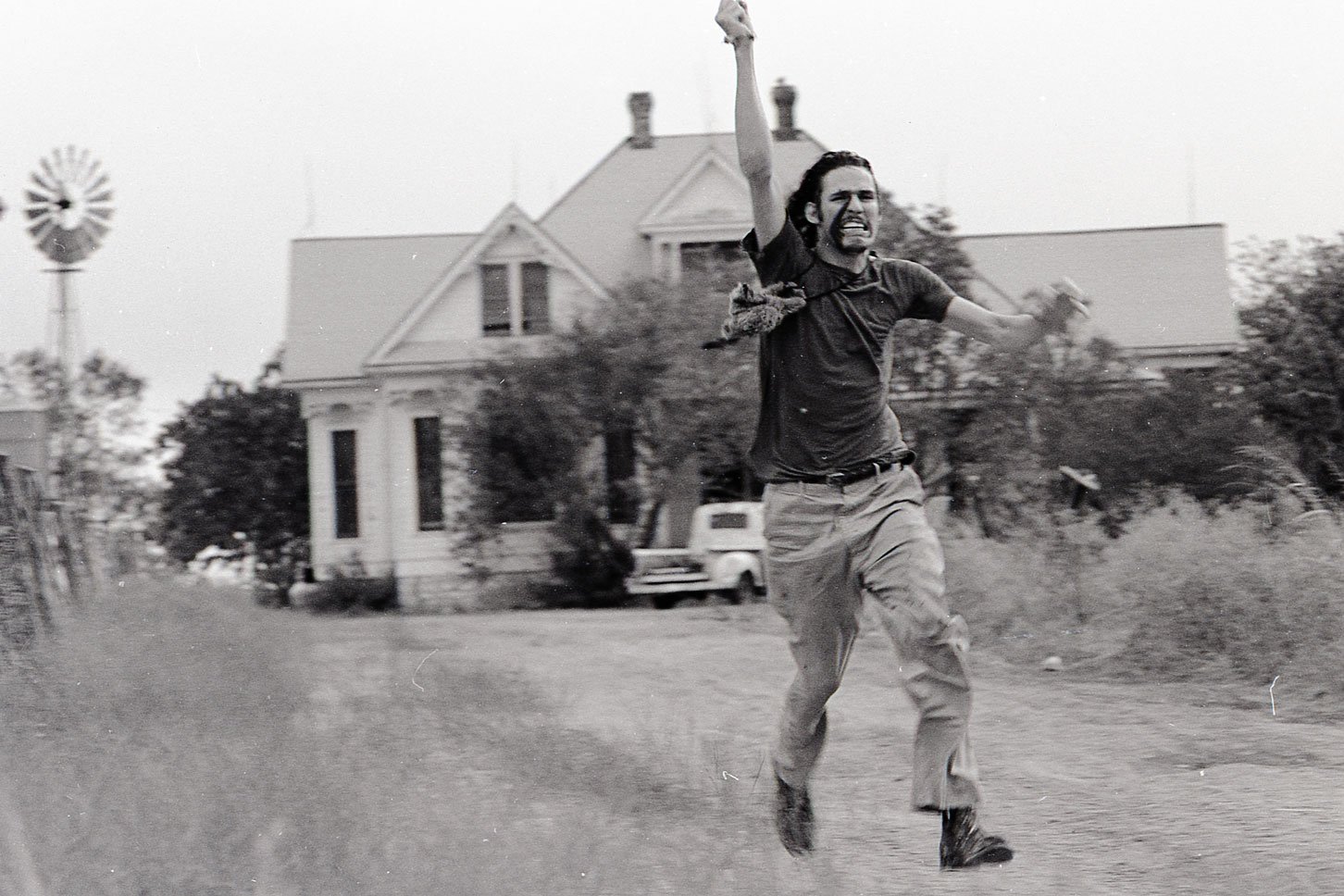

The shoot was littered with problems. From the outset shooting in the Texan summer meant that the temperature on set often rose to over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Bad enough on its own, the excruciating heat was exacerbated by the fact that the actors were not the cleanest of souls. For the sake of continuity while filming and in a bid to cut costs wherever they could, the director prohibited any of the actors from showering between takes, or even cleaning their clothes. The time and money that it would cost to provide extra costumes or dry-clean them in between shooting days, was a luxury that Tobe Hooper wasn’t willing to indulge his cast with.

The odour of the cast wasn’t the only smell that the crew had to battle with during filming. In a bid to up the ante and create a chilling atmosphere on set, Robert Burns, the art director, brought in hundreds of pounds of animal corpses in order to decorate the farmhouse set. The corpses, sourced from a local slaughterhouse, soon began to rot and petrify in the Texan summer heat. In an attempt to stave off the effects of decomposition, the art department began to inject the corpses with formaldehyde. However, in one occurrence, makeup artist Dottie Pearl mistakenly injected the chemical into her own leg. An incident that would come to define the haphazard and tense nature of the shoot.

“So on the day of shooting the dinner scene, a big dump truck pulls up at the house. It had one of these hydraulic beds and they dump all of these animal cadavers at the back of the house. A hundred at least. Dogs, cats, everything. They came from the city pound and had just been euthanized. It totally freaked everyone out, including me.”

Daniel Pearl, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s Cinematographer

After the completion of the shoot, director Hooper was met with the dilemma of how best to distribute the film. In sidestepping the traditional route of producing the film within the Hollywood machine, the crew had afforded themselves creative freedom, but at the price of no company wanting to touch them with a 10-yard stick. All except one: Bryanston Distributing Company. Through the connection of their producer, Louis Peraino, Hooper and his team were introduced to a company that would be willing to distribute the film while overlooking the graphic violence and extreme subject matter, the only catch being that they would have to exchange a large portion of the rights to the royalties. Having few options available, the team agreed, believing that they had at least acquired a valuable lifeline for the movie. What they didn’t know was that Bryanston, had ties to the mafia and through some “creative” accounting, almost every single member of the crew saw very little when it came to royalties.

Upon release, the film became a cultural phenomenon. Filmmakers, critics and the general public all gravitated to the unique portrayal of violence, alienation and isolation. The harsh and guttural mood aligned with an audience who were dying for stories that could take them to newer, darker places and themes that were reflective of the time that they were living in. This is not to say that all feedback was positive. The BBFC denied the film a certificate upon release when its chief censor James Ferman called the film “an exercise in the pornography of terror.” For the British film board, the film was made purely for its shock value, a provocative creation lacking in any artistic merit.

While they were not alone in criticising the film for its excessive violence, in retrospect it is noted that there was actually very little on-screen violence in the film. While filming The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Hooper constantly pushed for the film to retain a PG rating. He would go back and forth with classification boards looking for the exact criteria needed to keep his feature within the realm of PG. Hooper would only hint at violence, cutting away at the last second to allow the audience to fabricate the deaths put on screen. On second viewing you will notice that the most blood you ever see on screen is the scene in which the family prick the finger of Sally.

The legacy of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, can’t be understated. Like other classic films that set the blueprint for their genre, such as Blade Runner within the cyberpunk genre or Ring spawning a multitude of horror flicks in Japan, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was fundamental in building the foundations for the slasher genre. Without the menacing and hulking figures of Leatherface, there would be no Michael Myers or Jason. When asked about the impact of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre upon his filmmaking horror maestro John Carpenter stated, “It rode the knife edge of terror like no other. It pacified my soul. I went home and slept like a baby [after watching it.] Perhaps there is no greater compliment than that.

WORDS BY JAMES ELLIOTT