"CINE QUINQUI": A GATA Guide to Spain’s Underground Crime Films

The advent of the 1970s saw a monumental shift in the societal and political landscape of Spain; with the resignation of Francisco Franco marking the eventual fall of the military dictatorship that had come to define Spanish identity for the past three decades. With this disintegration of absolute control, came artistic freedom for film directors, who for the first time in almost forty years found themselves free of censorship and with the opportunity to explore themes and stories that had long been forgotten. “Quinqui”—pronounced as “kinky” coming from the Spanish word for “delinquent”—was a film genre that explored the chaos and savagery of the 1970s and 80s, born out of the post-Franco vacuum that existed in society at the time.

The fall of the fascist dictatorship and its transition to democracy did little to change the well-being of those who inhabited the poorest of neighbourhoods in Spain at the time. Graphic violence, casual sex, heavy drug use amidst police brutality and an explosive epidemic of HIV—Cine Quinqui gave a raw and harrowing portrayal of the everyday reality of young people in Spain’s most deprived areas.

Drawing influence from Italian neorealism and its focus on the working class, as well as the French New Wave’s rejection of traditional filmmaking techniques, Cine Quinqui dug even deeper into the lives of marginalised youths in Spain at the time. Led by directors such as José Antonio de la Loma (Perros callejeros 1977) and Eloy de la Iglesia (Navajeros 1980) the film-makers often found their actors on the streets, casting young people who in their everyday lives mirrored the crimes of their fictional counterparts. Sadly many of the stars of the genre would go on to meet premature deaths, often through either drug overdose or murder.

To celebrate an area of cinema that may be unfamiliar to many, here at GATA we’ve decided to make a list of some of our favourite films from the genre—a collection of exploitative tales that don’t ever shy away from the realities of a turbulent time in the history of Spain.

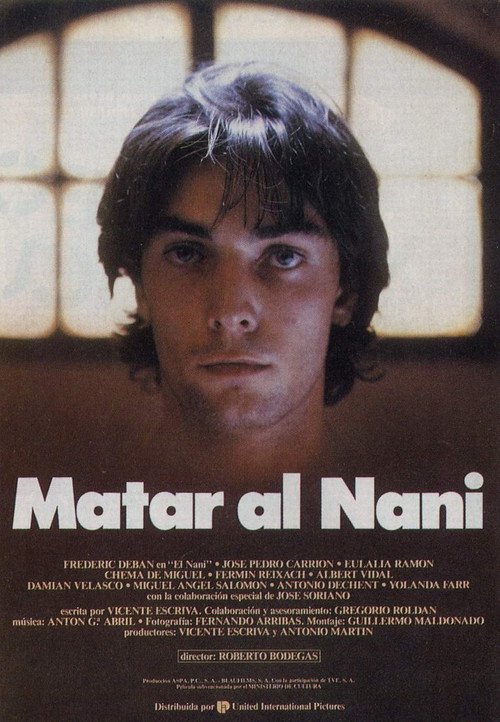

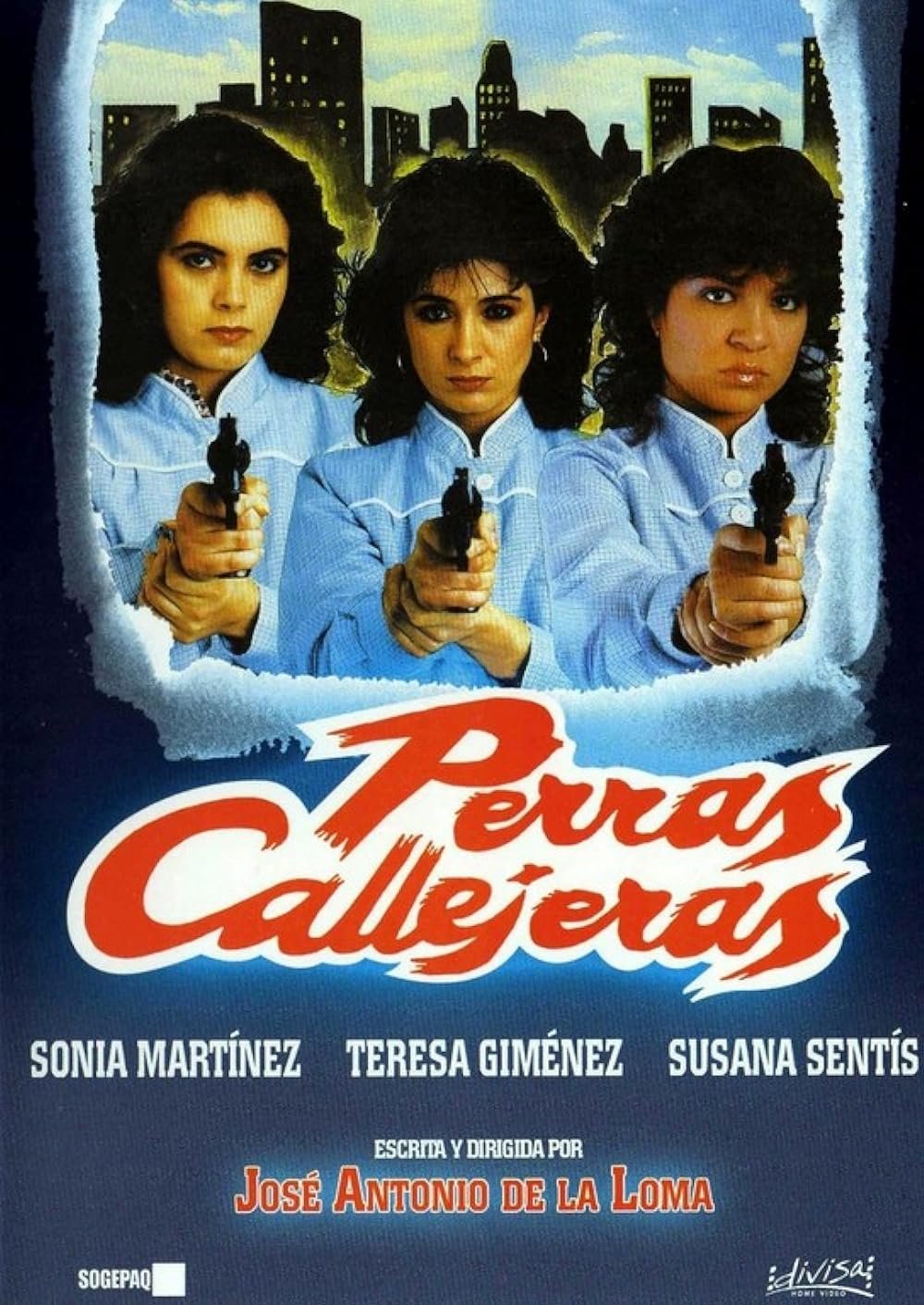

Perros Callejeros

José Antonio de la Loma (1977)

Perros callejeros or Street Warriors in English was directed by José Antonio de la Loma and was released in 1977. Regarded by many to be the earliest film in the genre of cine quinqui. Criticised by critics at the time for its b-movie aesthetic and below-par cinematography, the film sets out to tell the tale of a gang of 15-year-olds living in the suburbs of Barcelona as they terrorise neighbourhoods, committing crimes such as car theft, robbery and assault.

Emblematic of the genre that it would go on to inspire, Perros callejeros echos the themes and stylings of “A Clockwork Orange”, showcasing the cruel and violent behaviour of youth gangs while simultaneously holding them up against the equally cruel and manipulative behaviour of those in positions of power, such as the police. While the film hasn’t aged as gracefully as some others on this list, it more than makes up for it in its rawness and authentic energy. An essential entry into the genre and a must-watch for those looking to educate themselves in the movement.

Navajeros [Knivers]

Eloy de la Iglesia (1980)

Directed by Eloy de la Iglesia, Navajeros is a violent portrayal of youth culture bordering on social commentary. Considered by many as a classic entry in the genre, the film is a brutal exposure of the realities of the working class during the 70s and 80s pulling no punches in its violent depiction of life on the street.

Set within the slums of Madrid, Navajeros tells the story of José Manuel Gomez Perales, and his criminal alias “El Jaro” as he leads a gang of young criminals in a nihilistic quest in search of thrills, love, meaning and respect; often in a world that seems to be stacked against them. The film begins with the quotation “Men don’t become criminals because they want to, but have been driven towards crime out of misery and necessity” hinting at a world in which systems of control often dictate the behaviour of those at the bottom. However, the director’s raw and unfiltered portrayal of gang violence, prostitution and drugs, paints a murky and blurred picture of morality— often making it difficult to side with either the delinquents or those in positions of power.

El Pico [Overdose]

Eloy de la Iglesia (1983)

Conceived as a metaphorical tale to highlight the parallels between heroin addiction and the unease experienced in the “transitional” period between Franco’s military dictatorship and Spain’s new vision for democracy, El Pico tells the story of a friendship between two young men and their shared love for the substance that is heroin.

Set in the Basque Country of Spain, the film’s director Eloy de la Iglesia, makes use of a cold and abrasive neo-realist style to tell the story of his characters. The film largely centres on the relationships of the two young men as they try to find means of acquiring drugs, while hiding their lifestyle from their families. As the boys fall deeper and deeper into their addiction, the boys resort to crime and violence to keep feeding their cravings, eventually propelling them into a dramatic and heart-wrenching conclusion.

Coto de caza [Hunting Ground]

Jorge Grau (1983)

Directed by Jorge Grau and written by Antonio de Jaén, Coto de Caza (Hunting Ground) is a quinqui film that crosses the line into the realm of exploitation cinema, moving the focus from the delinquents and criminals, to the victims of their actions. While previous entries in our list looked to explain the structural forces put in place that have influenced young people into committing crimes, Coto de Caza unashamedly takes aim at a lenient legal system that often allows criminals to get away with their crimes.

The story centres on the main character of Adela, who makes a living as a defence lawyer for criminals. After successfully winning a case for some of her defendants she is mercilessly repaid for her deeds with the youths stealing her car and setting off to rob her country villa. What follows is a gripping social commentary that looks to convey the message that often when you fail to lock up criminals they end up recommitting their crimes. Bleak, gritty and thoroughly unpleasant, this is a film that still finds relevance in modern times through its cutting social commentary.

Deprisa, deprisa [Hurry, Hurry!]

Carlos Saura (1981)

A recipient of the Golden Bear Award at the 1981 Berlin Film festival for best picture, Deprisa, Deprisa is a film soaked in the spirit of Flamenco music and quinqui cinema. Directed by Carlos Saura, the film takes a sympathetic approach to a generation of lost youths. The film is an engrossing portrayal of an entire generation of youths lost in a period of existential uncertainty. Rather than sensationalise the graphic violence of their crimes, the film spends a considerable length of time following its characters as they engage in child-like activities and just simply hang out.

The film featured a cast of non-professional actors who were deep in the delinquent lifestyle. In fact during filming, a number of the principal cast were arrested for separate crimes, causing a stir amongst Spanish media at the time. Reaction to the film was mixed, with conservative media outlets criticising the film and accusing the director of glamourising the use of drugs and violence among young people. One outlet even went so far as to accuse the director of paying his cast in illegal drugs. The director, Carlos Suara replied by stating that his young cast had a much better idea of where to score drugs than himself.

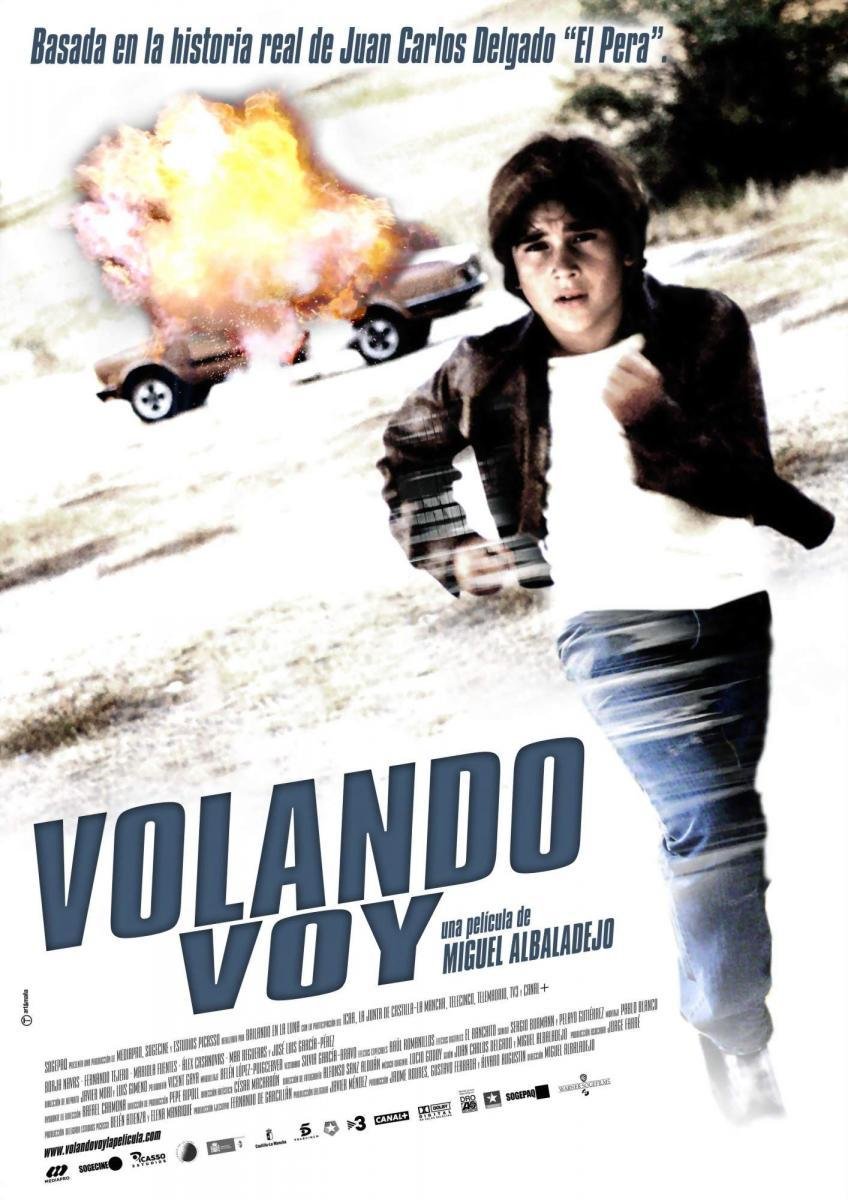

Yo, “El Vaquilla”

Jose Antonio de la Loma (1985)

Another film from director José Antonio de la Loma Jr, Yo, “El Vaquilla” is a film that takes inspiration from the real-life story of criminal Juan José Moreno Cuenca, who gained notoriety after beginning his career in crime at the age of nine. As a child Juan José Moreno Cuenca gained attention from the authorities after committing a series of car thefts—no mean feat considering the fact that he had to use cushions and stilts because his feet didn’t reach the pedals.

The film itself begins with the 23-year-old “El Vaquilla”—now a hardened criminal—finding himself behind bars and recounting the story of his life to journalist Xavier Vinander. Interestingly, this film attempts to trace the formative years of a criminal, attempting to dissect the reasons that might cause an innocent youth to transform into a hardened thug. Told through a series of flashbacks, the film highlights the absurd and contradictory nature of the police and their dehumanising behaviour, contrasting it with “El Vaquilla’s” desire for freedom in life, a desire that results in him recklessly breaking the law, and escaping prison on multiple occasions.

Drifting between narrative and documentary, Yo, “El Vaquilla” remains an interesting exploration of the identity of Romani people within Spain, and the at times complicated relationship they experience.

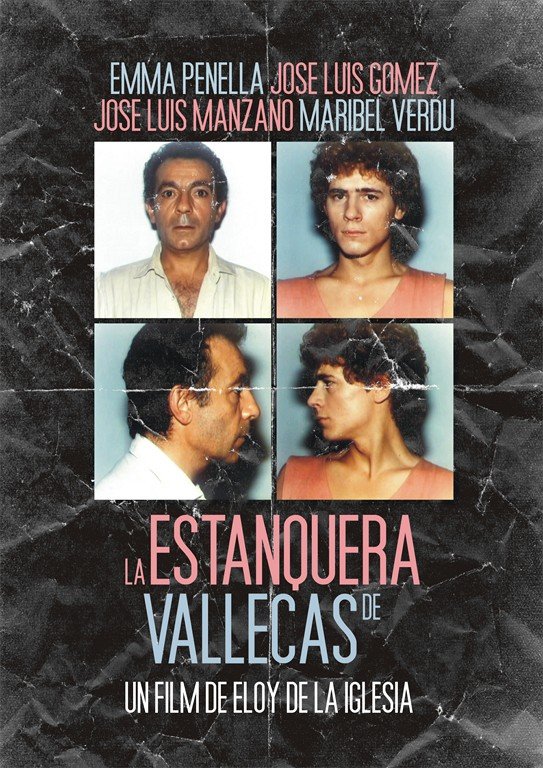

Colegas [Pals]

Eloy de la Iglesia (1982)

Eloy de la Iglesias’ Colegas is a gripping exploration of the camaraderie found among people in the face of dire situations. During the transitional period of Spain’s history, many young people found themselves disenfranchised and forgotten, spiralling downwards into the grips of real poverty. For many, this resulted in succumbing to the temptations of many activities that they wouldn’t have considered in the past; such as robberies, sex work and selling drugs. Colegas focuses on the story of two best friends Jose and Antonio whose desperation for money escalates after Jose manages to get Antonio’s sister pregnant.

The film is a classic quinqui film embodying many of the characteristics that made the genre so successful, such as an extremely low budget and actors with little to no experience. Interestingly the film acted as a metaphor of such, holding a mirror up to the sentiments and emotions that were experienced all over Spain during the period–and not just in the criminal rings. It was a chaotic and unstable time, where ordinary people were doing everything they could to make ends meet.

Maravillas

Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón (1981)

Maravillas is an inter-generational drama that focuses on the strained relationship between a teenage girl and her old and unemployed father. Maravillas lives with her father—an out-of-work photographer—who often steals money from her for his erotic vices. When Maravillas is gifted a valuable ring for her first communion from her Sephardic Jewish godparents, the ring suddenly goes missing and the number one suspect is unequivocally her father.

At face value the film reads as a story of the relationship between a daughter and father, the film can also be viewed as a discourse on the conflict between the “old” Spain and the “New”— or Franco’s Spain and a new democratic future. It echos a pushback from the younger generation as they look to understand their standing in history, and the potential loss and confusion they experienced, after years of conservatism and dictatorship. Like any dichotomy, neither side is absolutely right, but this film offers an interesting entry into questioning this particular dynamic.

27 horas [27 Hours]

Montxo Armendáriz (1986)

Directed by Montzxo Armendáriz, 27 horas is a tragic tale of friendship, love and addiction. Chronicling the final 27 hours of Jon, a twenty-year-old drug-addicted young man- the film explores his family, friends and passion for drugs over the course of a day, painting a murky and complicated picture of a life pulled apart by self-destructive passions.

7 vírgenes [7 Virgins]

Alberto Rodríguez (2005)

A more modern entry to the list 7 vírgenes carries forward many of the traditions that made cine quinqui so impactful in the first place. Youth apathy, violence and crime, all the essential ingredients are in place here to make a classic in the genre. The film follows the story of Tano, a teenager facing jail time as he is given 48 hours of freedom in order to attend his brother’s wedding. The film paints a bleak and cold picture of the youth experience of the blue-collar neighbourhoods of Sevilla. Nihilistic and brutal this is a story that doesn’t hold back.

Chocolate

Gil Carretero (1980)

Directed by Gil Carretero, Chocolate is an action-packed story of drug smuggling, gangsters and bravado friendship; that borders on the absurd with its outlandish activities. The title “chocolate” comes from the slang word for marijuana, and hints at the slight Cheech and Chong vibe of the tale, two out of their depths men, embroiled in an ever-escalating tale of trouble and mayhem. Essential viewing for any fan of cine quinqui.

More essential titles from the same genre